Interview with Steve Almond

- Lex Enrico Santí, LCSW, MFA

- Feb 1, 2009

- 12 min read

Pre-Sugar Podcasting and, gosh, 12 or so years ago--Steve and I corresponded on this interview. I'm struck today just how gracious and what a kind soul he was then--and still is.

And, weird, both his parents were psychoanalysts. The original interview is here.

Introduction to the Interview

by Lex E Santi

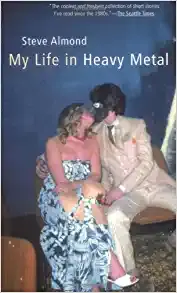

STEVE ALMOND HAS BEEN A LIGHTNING ROD IN THE LITERARY COMMUNITY SINCE 2002, WHEN MY LIFE IN HEAVY METAL HEAD-BANGED ITS WAY ONTO THE SCENE. When I first picked up his first short story collection I was struck by not only the power of his prose but his acumen towards the most basic human emotions. One story sticks out in my mind today, the story of a man in love with a staffer for the Republican Party. This modern day tale of Romeo and Juliet was funny, sexy and sad. It had an altogether modern and fresh outlook. In the story he vividly captures not only the nuance of political one-upmanship but also what became an ever-changing definition of truth and what was acceptable from one side of the aisle. The short story, How to Love a Republican (a title similar to Coutler’s How to Talk to Liberal, she being 6 years late and without a shred of grace) seemed to foretell a time when the basic human emotions may be neutered between political parties. I bring this all up, this seemingly roughshod rambling of political doldrums because we are now in an altogether different part of history. While we look towards tomorrow with hope, we must also accurately document the past; and that turns out to be, my friends, not only the work of journalism but fiction–yes–fiction: to speak for a generation. So, while it is still too early to tell the outcome of the Bush legacy, it is clear that the causalities are many and one of the employment causalities was Steve Almond. Almond did something in 2006 which few writers would consider ever doing: he quit his job. Stop—he quit his cushy teaching job as a professor at Boston College, publicly resigning in the Boston Globe. He did so as an act of conscience because the institution he worked for incentivized a morally corrupt politician. Simply put: he spoke truth to power. He was tarred and feathered by the right and faced an outpouring of criticism. Yet, even reading his letter of resignation today—some two and half years later I am struck by the wave of relief I feel that he did something. Read his letter. Read his short stories. His essays. Read his novel. Steve Almond is brash and stubborn. A father, now twice over. A Candyfreak. An essayist. A short story lover. Crass comes to mind. A teacher. A moralist. He comes from this brand of American writer who speaks loudly and worries later about what was said. He is an imperfect man living in imperfect times; where we must loan the banks money and when change happens suddenly and we cannot believe our eyes. His writing is sharp, cathartically honest and he has many many great years ahead of him (and if I can convince him, at least one solo novel). I’ll take Steve Almond over half a dozen other guys out there because with Steve Almond at least I know he's no bullshit.

Interview conducted by Lex E Santí via email

OUR STORIES:

Steve you’re the author of two short story collections, and a master in the field, My Life in Heavy Metal, The Evil B.B. Chow and other stories, the novel Which Brings Me to You and two non-fiction books, Candyfreak, and most recently Rants, Exploits and Obsessions (Not that You Asked). What draws you to work inside of non-fiction as well as fiction?

– Can I just say upfront that being identified as a “master” is a little disorienting. I’m more at the level of “pretty competent mid-list author” or “occasionally inspired pervert.” But okay, the genre thing. It works like this for me: if I want to engage my imagination and rig up a world for maximum emotional impact, I’m going with fiction. If I want to get at the truth about the world as it exists – via research, immersion, or concerted reflection on my own experiences – that’s a non-fiction gig. Plenty of overlap, of course. And a lot of this has to do with life circumstances. Back when I was in my 30s and living alone and eating food from cans and freezing my balls off at night, I could afford to write short stories all the live long day and it didn’t matter that I was earning 30 grand a year and had no medical insurance. Now that I have a family with little kids, that’s just not tenable.

OUR STORIES:

Rants, Exploits and Obsessions (Not that You Asked) REO(NtYA) covers a wide breadth of topics, from your greatest sexual failures, your obsession with Kurt Vonnegut to the inferno of Fox News (kudos to you brother, you smoked ‘em) what essay gave you the most trouble writing and why?

– The Fox News one was tough because it played to my weakness, a tendency to instruct the reader as to how they should feel and behave (as moral actors), which is totally fucking annoying and counter-productive. I managed to bleed some of that, but it’s still pretty didactic and as such a partial failure. The piece about sports fans was tough, too, because it came in at, like, 25,000 words, about 20,000 of which sucked ass. So I had to do a lot of butchering and suturing. When you write from your obsessions there’s always this risk that you just go on in a way that bores the puke out of anyone who isn’t obsessed about the same stuff.

OUR STORIES: Behind or ahead of the curve with technology?

– It’s kind of relative. So, like, way ahead of the curve if you’re comparing me to the entire world. But if you’re comparing me to college-educated 42-year-old dudes, probably a bit behind the curve. I never learned how to operate a fax machine. (Actually, that feels like something I might be proud of.) I only got a cell phone a few years ago. It’s not really technology I worry about so much as the direction it pushes consciousness.

OUR STORIES: You’ve been taken to task over your opinions regarding blogging from various sites online since you published your Salon.com piece–which I interpreted as a sort of a knee jerk amusement–and since that time you had (briefly) your own blog about being a father, what was that all about? Did it feel good joining the blogowagon for a while?

– Well, I told the website folks I wanted to be a columnist, but they were pretty insistent that I should do a blog and I discussed it with my wife and we decided that it would be a cool way to document our daughter’s first year or so and would be appreciated by our families. And it helped pay the bills. But I have to say: there’s a big difference between gushing about your kid for other parents and talking shit about authors without having read any of their work. The short answer is: the blog was fun while it lasted.

OUR STORIES: In REO(NtYA) you make a few mentions of generalizing about Americans: Page 30 “They liked the fighting. They liked gossiping afterward about the fighting. Simply put: They were Americans.” Page 233 “Really, she’s just a typical American young person, happily cocooned within her own radical naïveté.” Page 245, “I do believe that Americans will look back upon this era some day and discern the seeds of their own ruin.” So here’s my question, dude: I, for one am still basking in the post-Obama glow of the inauguration, I’m wondering if you feel things have changed because of the election, are you hopeful? Amused? Skeptical?

– I’m sort of skeptically hopeful. Obama’s going to try his hardest to undo the damage inflicted on this country (and the world) by the sham “conservatism” of the past four decades. That’s inspiring to see. But I remain pretty disappointed in America as a whole – even Obama. He talked in his inaugural speech about how us Americans should never have to apologize for our “way of life” and that he’ll make sure that way of life is defended. I’m sorry, but that’s straight from the Bush playbook. Go to any fucking non-Western country on earth and it becomes obvious within two seconds what spoiled brats Americans are. We should be apologizing every second of every day. Not saying that I’m not thrilled we have a real leader in the White House, but the problems we’re up against as a species are going to require radical amends, not incremental improvements.

OUR STORIES: I want to personally thank you for taking the steps you did to resigning from your post at Boston College, with going with your gut (as Oprah does with her books) and speaking truth to power. Steve thank you, I feel that you spoke for a generation of writers as Fitzgerald encourages us to do—not only in your fiction but in your poignant letter to the Globe resigning your position as adjunct professor at Boston College. Tell us about Steve Almond the professor and what you look for in fiction and whether you’re teaching now.

– I’m not teaching, though I do miss it like hell. I’m not sure how I was as a professor, though some students hated me. I gave my kids extra credit if they made me mixed CDs. Some of them appreciated that. And I gave a scary speech on the first day, to scare off all the meatheads. That was fun. As for what I look for in fiction, I’d say emotional danger is the central draw. I can do without “minimalist slice of life” stories. Frank O’Connor sums this up perfectly at the end of the “Guests of the Nation.” His last line – it deserves to be read in context – is the standard to which I hold stories.

OUR STORIES: Tell me about the Poker Buddy Test, which I understand is one of your methods of evaluating short stories.

– It’s just an internal standard I have when I’m writing a short story, which is to ask if the dudes I play poker with would get it. It’s not that I’m seeking to dumb down my work. But I like to be able to write in a way where people who aren’t voracious readers can pick up a story and not feel excluded. We’ve got enough people who view literature as some arcane undertaking, when it should be regarded as the ravings of mad men and women.

OUR STORIES: Received any hate mail from Jonathan Safran Foer since your column, “EXTREMELY MELODRAMATIC AND INCREDIBLY SAD”? Have you talked to him about it?

– No. Safran Foer’s doing just fine for himself. He’s a terrific writer. I only hope he’ll use his abundant talents in ways that feel less clever and melodramatic. I’m thinking of a guy like Chuck Klosterman. He’s this quirky/funny pop culture critic and he could have kept punching that ticket. But he decided to write a novel. And what’s inspiring is that it’s a really good book. He really loves his characters, and he gets them, and it shows. So that’s really what it’s all about with any writer: living up to your highest ambition. And my own sense is that Safran Foer is talented enough to write an important novel, but that he’d have to put aside certain tendencies that limit him and his work. I’m one to talk. I’ve failed to come anywhere close to my potential as a fiction writer. The fact that no one’s given my literary failings a serious grilling is merely a testament to those failings.

OUR STORIES: I’m a fan—I admit it. I adore My Life in Heavy Metal, (MLiHM) it’s such a refreshing collection of short stories and it is one of the rare collections that I re-read for inspiration. Tell us about the process of publishing this collection?

– An early version of the collection was rejected a bunch of times, which it probably deserved. Then I wrote a bunch of new stories and an editor at Grove actually got in touch and the collection I was able to give him was much stronger. I wanted to call the collection “The Body in Extremis,” but the folks at Grove wanted “MLiHM,” which they figured would appeal to younger readers. My editor had lots of suggestions, most of which I ignored. There are excesses of language, but it’s a pretty fair representation of who I was back then, as a writer and person. One thing I insisted on was the order of the stories. I wanted “Among the Ik,” which is a very traditional story, placed second, so critics wouldn’t just write the book off as being about sex. I don’t think a single critic mentioned that story.

OUR STORIES: The rumor was that you were given a paltry sum to go out and promote (MLiHM) and that you developed the reputation of a wild man because of your exploits in those years?

– Grove set up a whole shitload of readings, at my imploration, and gave me a couple of grand to help with expenses. I funded the rest myself. So it’s true that I slept on a lot of couches and smoked a lot of weed. I’ll let the rumors stand.

OUR STORIES: My copy of My Life in Heavy Metal is pretty worn out, it is an autographed copy and it reads:

Donna– Desire is the true human engine– Rev it. God Bless you for reading, Steve Almond.

Any chance I can send this copy to you and you can cross out Donna and put Alexis in there?

– Actually, I’ll burn Donna’s name. Whoever she is, she got an autographed copy of my book and then sold it. Did I mention how glamorous short story writing is?

OUR STORIES: We’re publishers of only short stories so I when I stumbled upon one of your essays, “WHY I WRITE SHORT STORIES” my interest was obviously piqued. You’re quoted as saying, “I believe the short story is the purest form of what we commonly refer to as storytelling, by which I mean the most intuitive, satisfying, and elegant of our narrative possibilities.” Word. You go on to list a number of other merits of the short story form and then state what you dislike about the novel form and go to say, “because novels, by contrast, often disappoint me.” And then, “Because, in the end, I don't care much for plot”. When I read this it reminded me of early Richard Bausch who began writing short stories and was quoted as saying that he “only began writing novels because he couldn’t sell his stories,” (Atlantic Monthly) and was something he later regretted having said. Looking back on that essay, and now having completed your first novel do you still feel the same way?

– No. The truth is, until I write a decent novel all by my lonesome, I’ll be pretty disappointed in myself. I’d like to be able to commit to a character for the long haul.

OUR STORIES: Your novel Which Brings Me to You, (WBMtY) was recently released. The novel was co-written with Julianna Baggott (Girl Talk) can you tell us how the project started? And how did you handle doing so logistically?

– Basically, Julianna asked me to write the book with her. And I eventually agreed. It was a dream collaboration throughout the first draft, and then it got rocky as we started to edit each other. We nearly quit a few times. Then we made up. And now we’re like an old divorced couple with joint custody of a kid we like a lot.

OUR STORIES: Sex. Go.

– What, you’re not going to buy me dinner first?

OUR STORIES: Reading your prose I’m constantly stuck by your sheer audacity in how you mine honesty. You let us examine every pore of who you are in your nonfiction and who your characters are in your fiction—it’s something of the old Woody Allen shtick of self admonishment/aggrandizement while at the same time there’s something always refreshing and hip to it. What influences of other writers, family, etc.. did you have to push your writing in this direction?

– My folks are both psychoanalysts, which should explain a lot. I’m basically incredibly grateful when I read work where I feel like the author is telling the truth in an unvarnished way about stuff that matters to them deeply. Doesn’t really matter what the prose style is, just as long as that brutal insight is present. So the influences range from Bellow to Austen to Forster to Barry Hannah and Lorrie Moore and George Saunders.

OUR STORIES: You did your MFA at UNC Greensboro, can you tell us about the time you spent there—you’ve described it as a place with a mattress and a bottle of cherry coke, what else comes to mind?

– Oh, just a lot of relationships that I managed to fuck up, or that managed to fuck me up. It was an unhappy time. I was so eager to learn and get better, but I kept pissing everybody off. I just remember being lonely and angry a lot. I did learn a lot, but, as the soul legend Howard Tate put it, “I learned it all the hard way.”

OUR STORIES: Our Stories is a peer review literary journal. Every story we receive we give some feedback on, no matter what, to encourage our writers. And our contest fees subsidize a small salary for all our staff members who not only read entries but give page-by-page feedback of the stories. Can you tell us what you think about this policy and about your own experiences early on with sending your work out?

– You guys are doing it right. It used to drive me nuts when I was sending work out that I’d get back these Xeroxed notes with no ink on them. It was like I was submitting to a corporation. Then I became fiction editor of the Greensboro Review and I realized that – even at small journals – the stories are being read by half a dozen people. And all those people have opinions about the stories. So I made it my policy to write letters to the top 100 stories. When possible, I had the editors and readers who were most moved by a story write the letter. And I tried to make sure we put ink any rejections where the story had even a shot of getting published. This just struck me as the decent thing to do. The irony is that reading all those stories, and thinking about why they succeeded and why they didn’t, was more useful to me than anything else I did in grad school.

OUR STORIES: Steve, thank you for taking the time to answer our questions. Congratulations on the birth of your daughter and I wish you nothing but the best; this has been a true pleasure. Anything else you’d like to share with us?

– Nope. Just thanks for reading my work and asking smart questions and I’m sorry if my answers felt dashed off. We’ve actually got a son now too, Judah Elijah, born in December. So no one’s getting much sleep these days. Other than Jude.

Comments